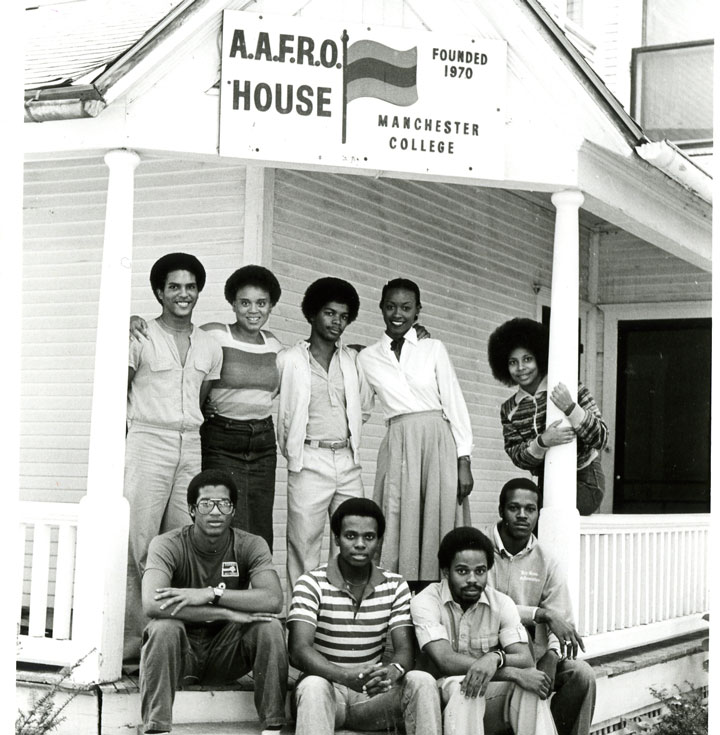

Manchester students pose on the porch of the original AAFRO House near the North Manchester campus.

Racism remains “the elephant in the room,” Glynn Hines ’73 told those attending Manchester University’s annual Martin Luther King Jr. Remembrance and Rededication Ceremony Feb. 4. “We need to talk to each other. … We need to have those open, frank discussions about how we feel.”

Racism remains “the elephant in the room,” Glynn Hines ’73 told those attending Manchester University’s annual Martin Luther King Jr. Remembrance and Rededication Ceremony Feb. 4. “We need to talk to each other. … We need to have those open, frank discussions about how we feel.”

Hines, a longtime city council member and civic leader in Fort Wayne, delivered the keynote address at MU’s commemoration of Dr. King’s 1968 speech at Manchester, the last speech he delivered on a college campus before his assassination.

This year also marks the 50th anniversary of AAFRO House, the founding of which Hines played a role as a Manchester student.

Hines came to Manchester as part of an expanded recruitment in the late 1960s to enroll more Black students. He recalled two fights that broke out between Black and white male students in October 1969.

“We didn’t know what was going to happen,” he said of the Black students. “We were deathly fearful of what might happen to us.”

So they gathered in Petersime Chapel and stayed there, negotiating with the administration to have a club, a place where they could go to feel comfortable, and an African-American advisor.

Their agreement led to at least two study committees and the eventual formation of AAFRO Club (Afro-Americans Forming Rightful Objectives, now Black Student Union) and AAFRO House (now the Jean Childs Young Intercultural Center), which opened in early 1971.

Hines remains “really proud” of that legacy.

Growing up in Fort Wayne, Hines had not heard of Manchester College until the late 1960s. Dr. King’s speech in February 1968 “was a big deal” and put Manchester on Hines’ radar. In 1969, King protégé The Rev. Jesse Jackson spoke on campus. “I decided then and there that I wanted to come to Manchester,” says Hines.

What he found, though, was a largely polarized student body. White and Black students didn’t know each other well and, for the most part, didn’t socialize with each other, Hines recalled. Except for in the classroom and among teammates on the football and basketball teams, there was little interaction.

It was a racially charged time “and very challenging as an African-American student.”

Hines described a more positive relationship with faculty, who were supportive and inclusive of Black students. Professor David Waas, for example, was a regular visitor to AAFRO House after it opened. Professor Ken Brown invited students to his home to discuss issues of the day. As Hines prepared to graduate from Manchester, faculty members helped him with funds to enter a graduate program at Temple University.

Manchester is much more diverse than it was when Hines was a student, but there is much work left to do, he said.

How much do you engage with people of other colors? Hines asked MU students. “You’ve got to reach out and communicate with other people.”

Invest in yourselves and others, Hines urged students. “Get to know your neighbor. Get involved in your community.” Use the Jean Childs Young Intercultural Center, he added, “to have those Black Lives Matter discussions.”

“We need to have an honest conversation about what’s happening in America,” said Hines, especially an effective national conversation about white supremacy and white privilege.

Communication will break down barriers between people and help dispel misunderstanding. “The Jan. 6 insurrection at the nation’s Capitol happened because of misinformation, Hines said. “You’ve got to talk to each other” in your dorms and in your homes.

Asked why he stayed at Manchester despite the turmoil, Hines credited his parents. No one in his family had graduated from college and they both told him, “You are going to do better than I did,” he said.

“What kept me going was I wanted that degree from Manchester College more than I wanted anything else. I was determined to graduate.”

By

Melinda Lantz ’81